By Marc Tellez and Lee Jarvis. Proofreading and editing by Claira Whicher.

For the restart of the Osteopathyst I wanted to make a point of interviewing graduates of the Canadian Academy of Osteopathy (CAO). I’ve found that spending any time at all with my colleagues has benefited my understanding and development of Osteopathic Manual Therapy. As such, it has become one of my goals to highlight the unique methods and thought processes that these practitioners “bring to the table” (pun intended). On December 21st, 2023 I visited Marc Tellez (M.OMSc) in his office in Hamilton, Ontario. Marc has been a graduate of the CAO since 2017. Since his graduation he has taught Inductions, History, Student Clinic, Ethics, Quality and Professionalism, with a current role in curriculum integration. Marc is a gifted speaker and lecturer which made our interview easy to start and difficult to end when it was time.

At the commencement of the interview, I started with a simple question: what interests you currently in your hands on practice? This question took roughly 1.5 hours to answer and I enjoyed every minute of it. Though we covered many topics, some of which will be turned into articles at a later time, Marc made a point of emphasizing the idea that the practitioner should attempt to get the most out of every position on the treatment table. At the Canadian Academy of Osteopathy (of which Marc and Myself are both instructors), it is often taught to the student that you should be able to work on any region of the body in any position for any reason (aka lesion, aka somatic dysfunction). What the student typically comes to understand as the goal of practicing this multi-positional competency is to be capable of comprehending anatomy in three dimensions and to understand the consistency of the body’s position when in dysfunction. These are very valuable lessons, and completely worth the time it takes to learn.

What does not always occur to the student, and often takes quite some time for the graduate to understand, is that skill with leverage in any position often reduces the patients need to move positions, saves time in treatment, and as well creates more opportunities for learning. Reducing the number of movements or position changes required of the patient over the course of a treatment can be very important when working with the acutely injured or elderly patient. In the case of acute injury, such as a back strain, switching positions frequently further irritates the injured area. The more irritated the injury becomes, the harder it is to calm the region, reduce the pain, and the harder it is for the patient to trust your work. Though not always the case, many elderly patients will find it a significant expenditure of energy and take significant time to move from one position to another. For the busy practitioner, saving time is always a goal. Even saving a few minutes with every single patient potentially allows one to see more patients per day or simply allows you to take a much-needed coffee break.

All of the above are great reasons for competency with many body positions on the table. However, staying consistently interested, questioning, and constantly learning from your work provides a deep mental satisfaction in practice that cannot often be paralleled. Furthermore, this type of focus and problem solving often results in better outcomes for the patient, which is the reason we have the opportunity to learn in the first place.

According to Marc, much of this development of positional leverage can be done through alternating directions of leverage as well as experimentation with patient active maneuvers. Marc demonstrated several examples to me and of those unique applications I’ve chosen to explain and illustrate 3 in full. Marc wanted to make clear that he does not “own” and did not invent these methods as one cannot ever truly own or copyright applied anatomy. As with all things Osteopathic these methods should only ever be applied safely by a trained professional.

1. Temporalis Fascia Through the Arms

The patient is in the supine position.

The palms of the practitioner are placed firmly on the temporalis fascia regions and a slight superior (towards the practitioner) traction is created to the point of barrier. This alone if held long enough can be considered short lever myofascial release.

The patient is then instructed to reach downward with their arms, using their whole arms, from shoulders down to the fingertips. It may help to instruct the patient to slowly “walk the fingers down the table” as this cues the inferior direction of the arm to those without anatomy training.

The arms moving downward creates a pull from the acromioclavicular region, through the traps and platysma, through the mandibular and facial fascias, into the temporalis region.

As the tension builds, the practitioner will feel a downward pull in their hands. This is a significant pull and is much easier on the practitioner than simply pulling with the hands,

and very likely the patient will be pleasantly surprised that their arms are so apparently connected to the sides of the head.

This is a simple and useful method to lengthen and integrate the lateral fascias of the upper body that does not require the practitioner to stand up and manually hold the skull, while pulling down on the arm themself.

2. Supine Arm Abduction with Traction and Patient Active Bent Knee Oscillation

Whether done with one arm or two this is a relatively common maneuver in the Osteopathic world and allows for a wide range of leverages to be applied and altered quickly and easily.

In Marc’s words, it’s important “not to waste a position” and this position/leverage can be easily varied to suit the needs of the patient with only slight changes in the arms. More importantly it is easier on the practitioner as the need to move around the table is considerably less while still achieving the same result. For this method the patient is on the table in the supine position

Both arms are grasped at the distal forearm or wrist and then abducted up to the sides of the head.

Traction is added gently by the practitioner leaning back. In general, this position elongates the lateral sides of the body as well as many of the spinal fascias. A point can be made regarding the Latissimus Dorsi muscle (the “Lats”) here as with flexed arms/shoulders the Lats are significantly elongated. The Lats attach as low as the lumbar spine and iliac crest so this covers the majority of the trunk.

The variation component occurs in this method by raising the arms up or down in relative shoulder flexion and extension, as well as with lateral/coronal motion in adduction and abduction. As the arms move more superiorly into shoulder flexion the pull of those arms tends to generally create more spinal extension. This is particularly true in the thoracic spine, however because of the Lats is it possible for it to occur in the lumbar spine as well.

Part of the reason spinal extension is generated by this movement is because the thoracic spine favours flexion and the table works to resist this naturally. Using the arms in this way works to extend the flexion of the thorax over the flat and fixed table.

As the arms are brought off the midline or into a more abducted position this creates pull in on the lateral sides of the body through the coronal plane.

Bilaterally this line of pull tends to create general traction however unilaterally (single sided) we can encourage more specific side-bending. In combination of arm flexion and abduction we can get quite specific to more local regions of the body without direct contact on these areas.

To add some significant strength to the leverage, we can then add oscillation (movement back and forth) of the legs. When working with the upper body, the lower body is almost always a clever and viable additional lever as the weight and strength of the legs tend to be much more so than the arms.

In this case, the legs are brought into a bent/flexed position so they rest comfortably on the table. The patient is instructed to bring the knees to one side or the other as needed.

Dropping the legs to the side creates lengthening of tissues unilaterally (on that side).

This will assist the leverage generated in the upper body by adding to the existing direction of force being generated. This same method can also utilized for cross-body work if a single sided arm is pulled deeply into enough.

If the patient is capable, it is better still to have them slowly and smoothly take their legs from side to side to create a gentle on/off pressure to the fixed point/area of treatment. This allows the barrier to be approached safely as it is gradually and at least partially mediated by the patient’s comfort, performing the movement only as deeply as they can tolerate. Another advantage of this kind of patient active maneuver is that it’s easy for most any patient to do as it requires only general movement on their part.

3. Side-Lying MFR True Leg

We tend to associate the side-lying position with some of the biggest leverages generated in manual therapy treatments. Most commonly we see the side lying position utilized in the variously named maneuver wherein the leg is dropped off the table and the arm and thorax are rotated posteriorly (call it what you will).

But in the spirit of “not wasting a position” Marc showed me a simple positional access to the true leg/posterior tibial area that I had honestly never thought of on my own. With the patient in the side lying position, the top leg is flexed at the hip enough to expose the bottom leg (leg on the table).

The tibia of the bottom leg is located and the practitioner gently presses the space between that and the Gastrocnemius and Soleus muscle

The region is worked from top to bottom and extra time is spent as needed on the more difficult/rigid areas.

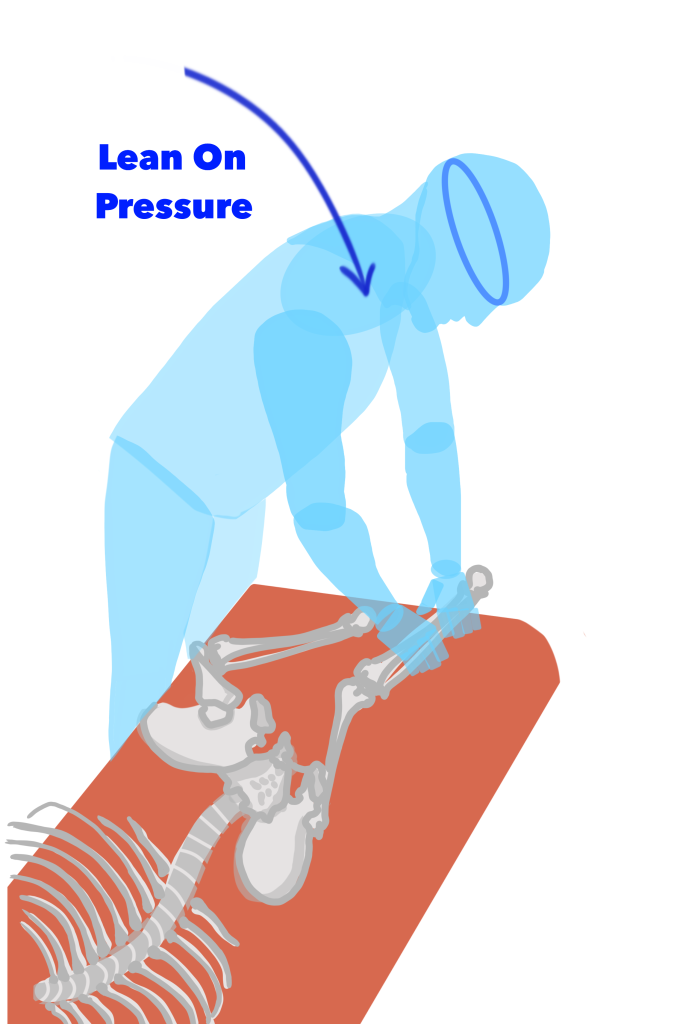

The intention here is to gently create a small amount of separation/space between bone and fascia on a angle not normally thought about or accessed.

With the position of the patient on the table and the superior position of the practitioner above the table, this maneuver allows the practitioner to easily drop down onto the leg which can easily generate power with little need for muscular force. The fact that the neurovascular passageway in this region for the posterior tibial supplies runs along this same path is worth noting.

As with all my colleagues, I had a wonderful time talking about Osteopathy and would like to thank Marc again for so kindly allowing me into his office and demonstrating his impeccable skills.