By Wayne Oliver, M.OMSc and Lee Jarvis, M.OMSc.

Proofreading and editing by Kiefer McQuillan.

Wayne Oliver graduated from the Canadian Academy of Osteopathy (CAO) in 2017 and is currently the Director of Labs at the CAO.

I interviewed Wayne on June 13th, 2024. You can see the first article based on my interview with Wayne here.

During our conversation the topic of being effective and efficient came up. This is a fairly normal concept for Osteopathic practitioners to talk about as saving time in treatment is nearly equivalent to saving physical effort. When the topic of efficiency in manual applications comes up it almost always turns to the concept of “less is better.” As Osteopathic practitioners, we should attempt to do less in the form of physical exertion as well as deliver the minimal amount of treatment necessary to generate a lasting, beneficial effect for the patient. This topic comes up frequently within the general Osteopathic community because it benefits both the patient and practitioner in a number of ways.

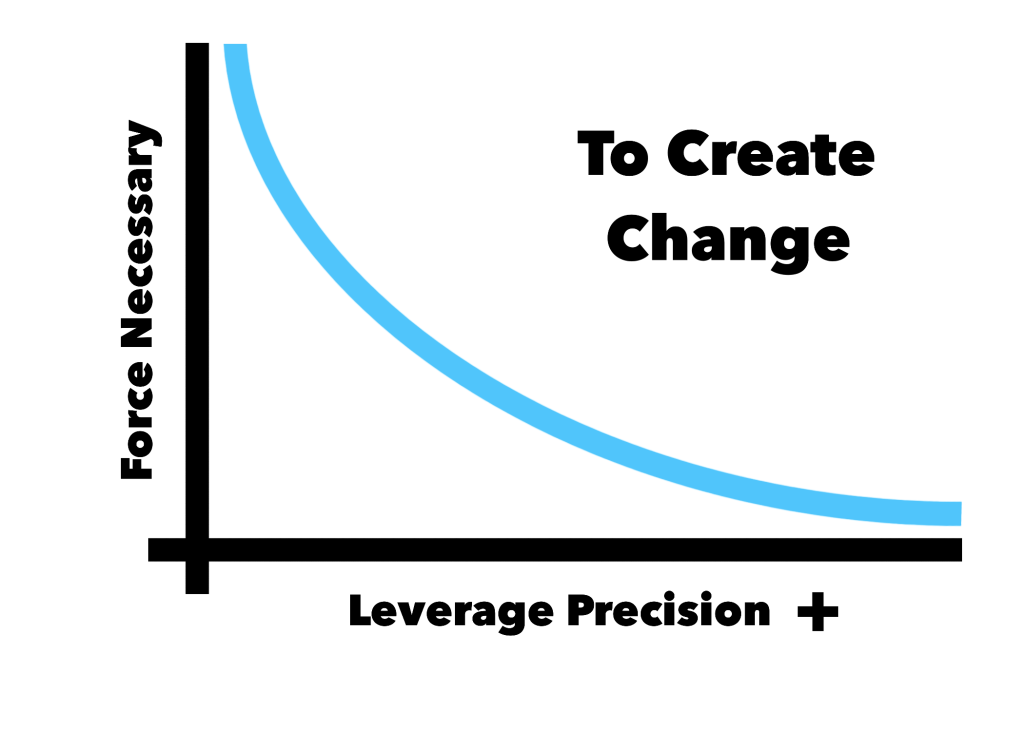

As mentioned in the previous articles with Wayne, his health was not good at the time of this interview and he was especially motivated to consider how much energy he could safely expend without exhausting himself. Wayne stated that when working to improve efficiency we should always remember how powerful long leverage can be when done well, and that the mental effort expended in developing long leverage is an excellent return on one’s investment into it. Due to its power, long leverage can be incredibly effective for our work or it can be dangerous if used improperly. Understanding this potential to help or harm is of equal importance to the practitioner; they must focus on developing the palpatory capacity to determine when they’ve gone too far into the barrier (past the point of tissue irritation and/or damage). Wayne and I quickly agreed that the more skilled you become with leverage the less force you will need to use to accomplish the intended work. To be more specific, with more skilled leverage, as little force as possible should be used in that leverage system.

Using less force will most often create a more beneficial effect than if you used more force, even if it were safe to use more.

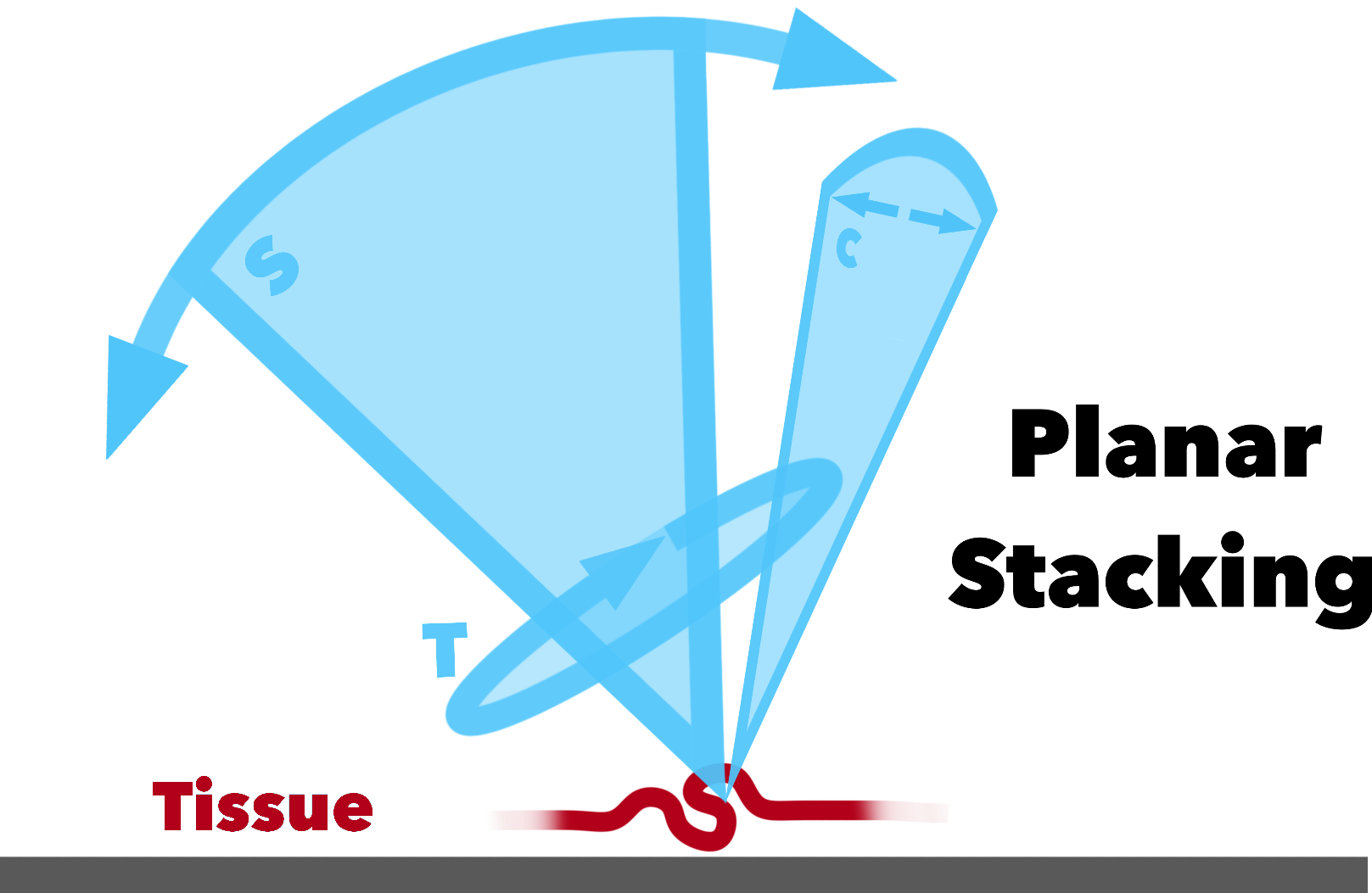

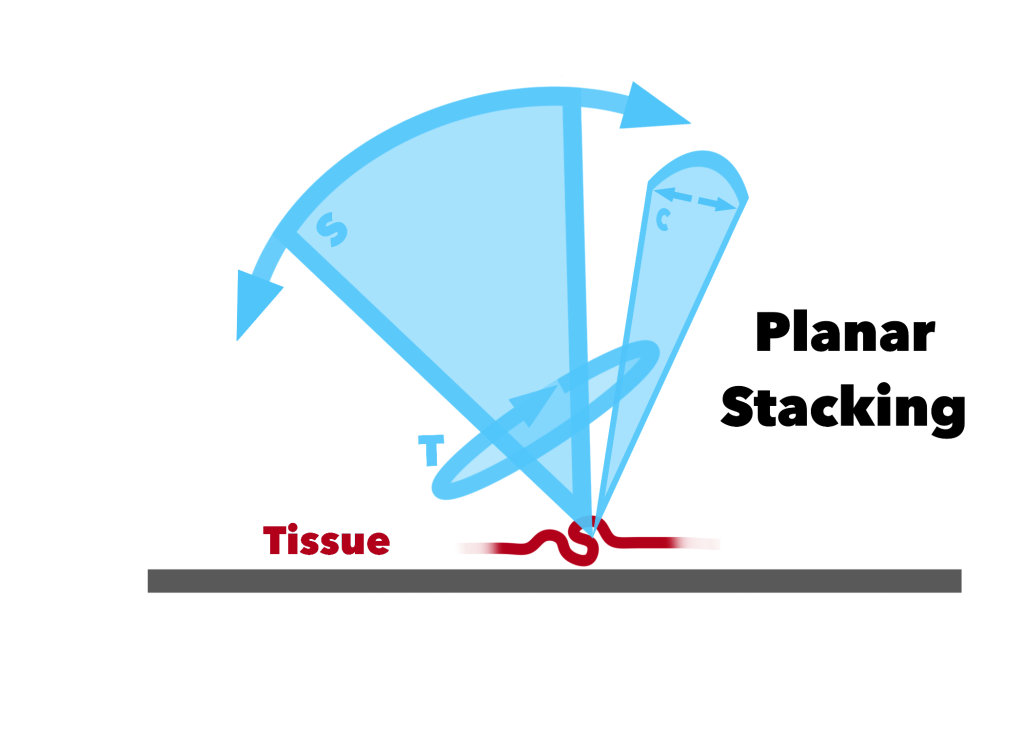

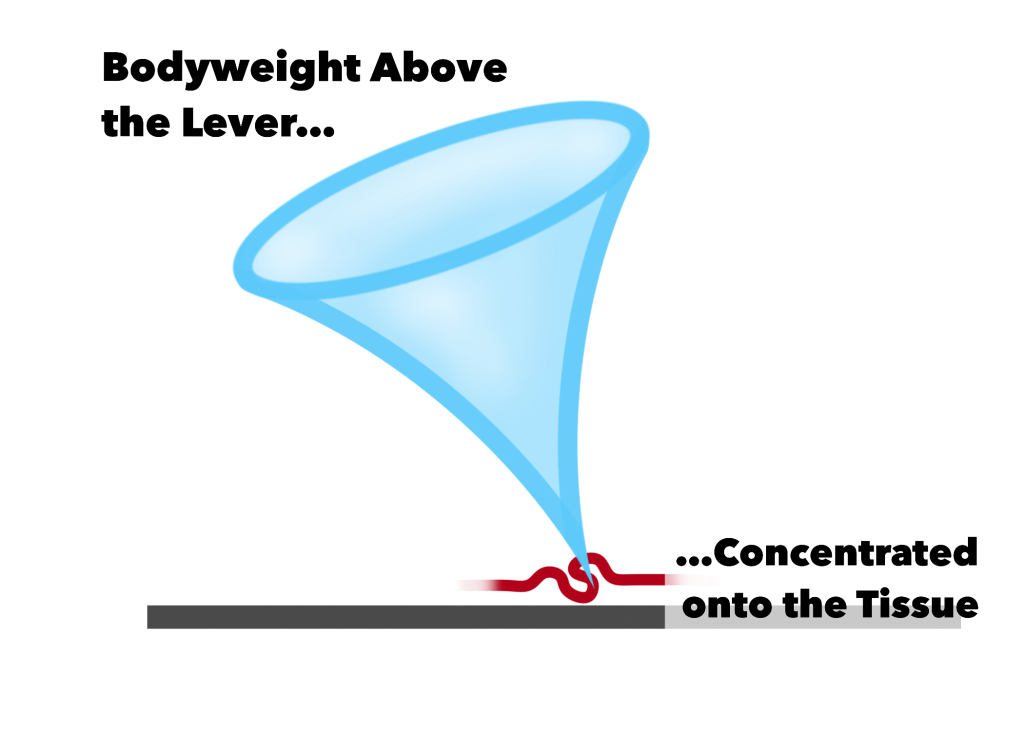

Using one part of the body to move another part is perfectly normal as it happens constantly in human movement. Long leverage is the body’s preferred way to move as it better distributes load along the involved structures and therefore reduces significant pressure on any one particular area. Comparatively, isolating force/load on a specific spot would increase the tendency to tear or break the involved tissues. In Osteopathic practice we take advantage of this natural long leverage as it will, in addition to being powerful, be less resisted by the body. Over time, the better we become with creating leverage the more planes we are capable of stacking into that lever, and the more specific we can be to the direction of restriction.

Consider that when generating long leverage all of the weight and all of the moving weight created can be directed into much smaller parts (a circular movement, for instance). To place that leverage and weight on that small, unmoving part is the goal; however, we should consider that leverage can rapidly turn from encouraging movement within a normal range to creating tissue irritation and/or strain.

Wayne explained that utilizing a single plane of motion often generates the necessary leverage for treatment. Single plane movement often does effective work when paired with a solid fixed point to direct the leverage. While not always the case, if the major area or direction of restriction in the tissue is within one particular plane, then that one particular plane is often all that is needed to address that restriction. Wayne said that he will add other planes as needed and that, for example, usually this is as simple as adding a small rotation or side bending to a flexion or extension.

Once we’ve achieved precision with leverage, it often doesn’t need to be much more than the generation and sustained holding of that leverage (as opposed to continuous movement). Further, Wayne said to remember that even in the treatment of a joint or boney region we are still considering the fascia/connective tissue’s flexibility. The related fascia, the connective tissue that surrounds the joint in this case, invests into the joint and forms the joint capsule. The joint capsule directly attaches the bones of the joint together and contains the synovial fluid within. Even the outer layer of the bone, the Periosteum, is connective tissue with its own relative flexibility. In that way, the fascial treatment is a form of articular (joint) treatment, and when fascial treatment is done effectively we should see a change at the level of and in the movement of the joint.

When we reached the subject of what to do after completing the treatment, Wayne said, “treat’em and street’em.” Once I’d finished laughing, I asked if Wayne had come up with that expression himself. He said he thought he had, but wasn’t entirely sure. I’m of the opinion that he did as it represents his straight forward way of communicating. Regardless of the expression’s originator, in its comedy and simplicity there are some practical clinical points. This expression of “treat’em and street’em“ is the idea that you should do a good job, in a reasonable amount of time, and send the patient on their way. Performing your Osteopathic job well is a larger subject than can be contained in a single article, though in context, Wayne was also referring to the conversation as described in the previous paragraphs on leverage.

“A reasonable time frame” means we are treating the patient within a time limit/appointment length that considers the average patient’s busy lifestyle (and how little time we all often have). As practitioners, we should be aware that few people can spend all day at our office, for some even 45 minutes is pushing it. “Sending the patient on their way” is both in reference to respecting the patient’s time, but as well, knowing that the patient must take on the treatment throughout their daily lives. We must remember that usually the patient cannot completely change their work and family life just for the purpose of recovery. Patients are only in your office for a short time and will be out “in the real world” for the rest of their week, hopefully, after your treatment, they will be able to integrate more pain free movement into their life. It is then expected that you see the patient for a follow up appointment within a reasonable timeframe and with respect to their life and availability.

Our conversation continued for some time after this, the subjects of which will be covered in part 2 of this article.